Common Gateway Interface (CGI) is a computing interface protocol that allows web servers to execute an external application, often to handle user requests.

Such applications are typically written in a scripting language known as CGI scripts, but they may also comprise compiled programs.

A representative example occurs when a Web user submits a Web form on a CGI-enabled web page. The data from the form is sent to the Web server as part of an HTTP request with a URL identifying a CGI script. The Web server then begins the CGI script in a new computer process and passes the form data. The CGI script returns the output, typically in HTML form, to the Web server then transmits it back to the browser to answer its request.

CGI, being developed in the early 1990s, was the first approach to be in worldwide utilization for making Web pages interactive. Despite still being used, CGI is wasteful compared to newer technologies, which is the reason for its supplantation.

When was invented?

On the www-talk mailing group in 1993, a team from the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) established the standard for invoking command line executables. Other Web server developers quickly gave acceptance, and it has remained a standard for Web servers ever since. In November 1997, Ken Coar headed a workgroup to formalize the NCSA definition of CGI. This study culminated in RFC 3875, which defines CGI Version 1.1. The RFC specifically points out the following contributors:

• Rob McCool (the NCSA HTTPd Web Server’s author) • John Franks (the GN Web Server’s author) • Ari Luotonen (the CERN httpd Web Server’s developer) • Tony Sanders (the Plexus Web Server’s author) • George Phillips (the University of British Columbia’s Web server maintainer)Previously, when CGI programs were under development, it was usually in the C programming language. RFC 3875, "The Common Gateway Interface (CGI)," says that environment variables "are accessed by the C library procedure getenv() or variable environ."

CGI derives from the early days of the Internet when Webmasters desired to link legacy information systems like databases to their Web servers. The server was the one to run the CGI software, which served as a "bridge" between the Web server and the legacy information system.

Purpose of the CGI specification

Every Web server uses HTTP software, which answers to web browser requests. The HTTP server often has a directory (folder) designated as a document collection - items that can be transmitted to Web browsers linked to this server. For instance, if the Web server's domain name is example.com and its document collection is kept in the local file system at /usr/local/apache/htdocs/, the server will respond to requests for http://example.com/index.html by transferring the (pre-written) file /usr/local/apache/htdocs/index.html to the browser.

For dynamic pages, the server software may postpone requests to different programs and feed the results back to the requesting client (most of the time, a Web browser that visualizes the page to the end-user). Scripts were popular in the early days of the Internet because they were compact and written in a scripting language.

Typically, such programs require adding some extra data with the request. For example, in the case of CooliceHost client area being written as a script, the script would require knowing if the user is signed in and, if so, under what username. The role of this information is to determine the material at the beginning of a CooliceHost client page.

HTTP allows browsers to provide information to the Web server in various ways, such as the usage of part of the URL. This information must then be passed to the script by the server software in some way. In contrast, when the script returns, it must give all of the information necessary to the HTTP for a response to queries: the HTTP status of the request, the document content (if available), the document type (for example, PDF, HTML, or plain text), and so on.

Previously, different server software would transmit this data with scripts in various ways. As a result, even if the information being transferred was the same, it was impossible to develop scripts that would operate unchanged for different server software. As a result, there was a decision to designate a method of transferring this data: CGI (the Common Gateway Interface, as it defines a common way for server software to interface with scripts). CGI scripts are web page generation programs called by server software and function under the CGI specification.

This specification was soon accepted and is accessible by all popular server software, including IIS, Apache, and (with an extension) node.js-based servers.

The first usage of CGI programs was to handle forms. HTML forms contained an "action" element and a button labeled as the "submit" button at the start of HTML. When the submit button is pressed, the URI defined in the "action" property will be transmitted to the server, along with the form data as a query string. If the "action" specifies a CGI script, the CGI script will be performed, producing an HTML page.

Using CGI scripts

A Web server's owner can specify which CGI scripts should handle which URLs.

That is typically accomplished by designating a separate directory inside the document collection as housing CGI scripts — the title of this folder is frequently cgi-bin. On the Web server, for instance, /usr/local/apache/htdocs/cgi-bin could be a CGI directory. When a browser requests a URL that points to a document within the CGI folder (e.g., http://example.com/cgi-bin/printenv.pl/with/additional/path?and=a&query=string), the HTTP server executes the specified script then passes the output to the Web browser rather than simply sending that file (/usr/local/apache/htdocs/cgi-bin/printenv.pl). That is, anything sent to standard output by the script is routed to the Web client rather than being displayed on-screen in a command window.

The CGI specification, as previously stated, describes the sending of extra information given with the request to the script. For example, if a slash and additional directory name(s) are attached to the URL directly after the script name (in this case, /with/additional/path), that path is saved in the PATH INFO environment variable before invoking the script. If parameters are passed to the script via an HTTP GET request (a question mark attached to the URL, followed by param=value pairs; for example,?and=a&query=string), they are saved in the QUERY STRING environment variable before executing the script. Parameters submitted to the script via HTTP POST are given to the script's standard input. The script could then receive these environment variables or information from standard input and adjust to the request made by the Web browser.

Example

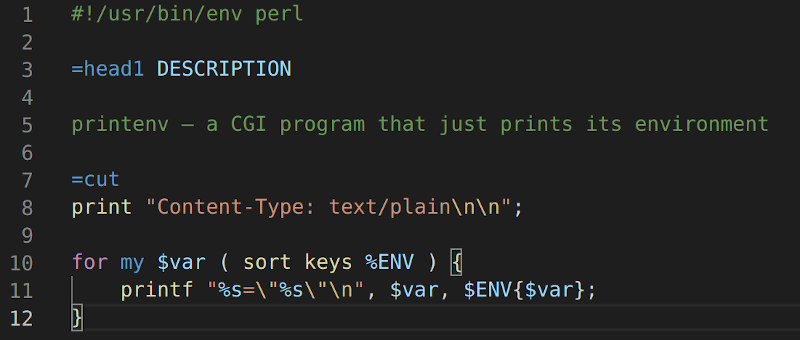

The Perl program below displays all of the environment variables given by the Web server:

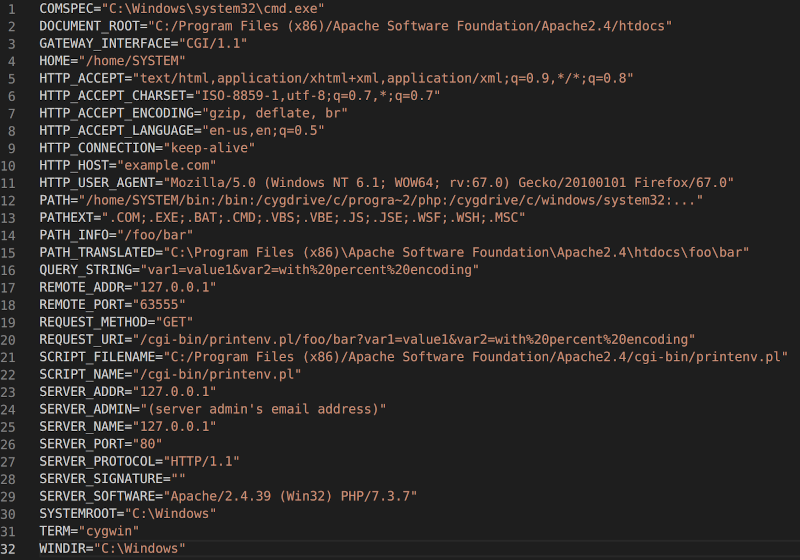

A 64-bit Windows 7 Web server running cygwin gives the following information when a Web browser requests the environment variables at http://example.com/cgi-bin/printenv.pl/foo/bar?var1=value1&var2=with% 20%20encoding:

The CGI standard defines some, although not all, of these variables. Some, such as PATH INFO, QUERY STRING, and those beginning with HTTP_, transmit information from the HTTP request along.

The environment reveals that the Web browser is Firefox operating on a Windows 7 PC. The Web server is Apache working on a Unix-like system, and the CGI script is called cgi-bin/printenv.pl.

The application can then create any content and write it to standard output, which the Web server would subsequently send to the browser.

The environment variables supplied to CGI scripts are as follows:

• Server specific variables:

◦ SERVER_SOFTWARE: name/version of HTTP server.

◦ SERVER_NAME: host name of the server, may be dot-decimal IP address.

◦ GATEWAY_INTERFACE: CGI/version.

• Request specific variables:

◦ SERVER_PROTOCOL: HTTP/version.

◦ SERVER_PORT: TCP port (decimal).

◦ REQUEST_METHOD: name of HTTP method (see above).

◦ PATH_INFO: path suffix, if appended to URL after program name and a slash.

◦ PATH_TRANSLATED: corresponding full path as supposed by server, if PATH_INFO is present.

◦ SCRIPT_NAME: relative path to the program, like /cgi-bin/script.cgi.

◦ QUERY_STRING: the part of URL after ? character. The query string may be composed of *name=value pairs separated with ampersands (such as var1=val1&var2=val2...) when used to submit form data transferred via GET method as defined by HTML application/x-www-form-urlencoded.

◦ REMOTE_HOST: host name of the client, unset if server did not perform such lookup.

◦ REMOTE_ADDR: IP address of the client (dot-decimal).

◦ AUTH_TYPE: identification type, if applicable.

◦ REMOTE_USER used for certain AUTH_TYPEs.

◦ REMOTE_IDENT: see ident, only if server performed such lookup.

◦ CONTENT_TYPE: Internet media type of input data if PUT or POST method are used, as provided via HTTP header.

◦ CONTENT_LENGTH: similarly, size of input data (decimal, in octets) if provided via HTTP header.

◦ Variables passed by user agent (HTTP_ACCEPT, HTTP_ACCEPT_LANGUAGE, HTTP_USER_AGENT, HTTP_COOKIE and possibly others) contain values of corresponding HTTP headers and therefore have the same sense.

The software sends the output to the Web server in the standard output form, starting with a header and ending in a blank line.

The header is encoded similarly to an HTTP header and should indicate the MIME type of the returned content. The headers, supplied by the Web server, are usually sent back to the customer along with the response.

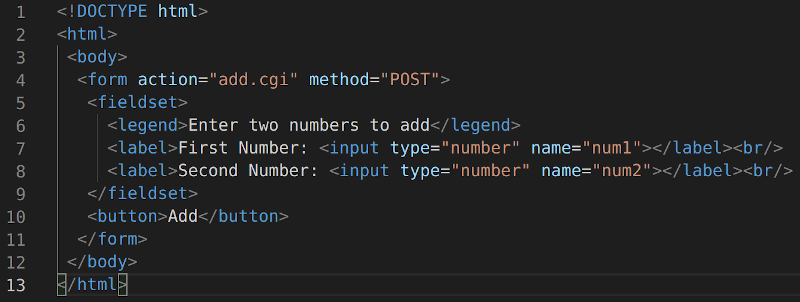

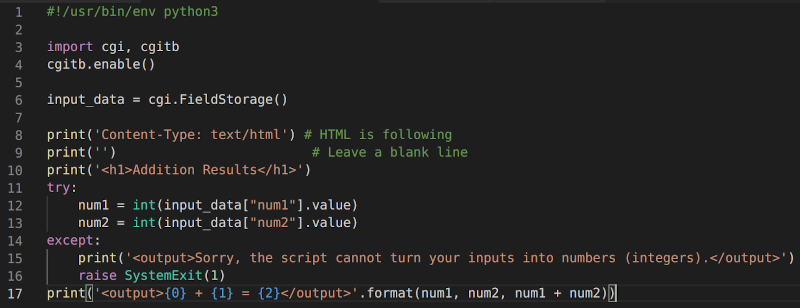

Here is a basic CGI program written in Python 3 and HTML, which handles an uncomplicated addition problem.

add.html:

add.cgi:

This Python 3 CGI software reads the HTML inputs and adds the two integers together.

Deployment

A CGI-enabled Web server is configurable to understand whether a URL acts as a reference to a CGI script. A favored practice is to place a cgi-bin/ folder at the root of the directory tree and treat any executables within this directory (but no other, for security reasons) as CGI scripts. Another common standard is to utilize filename extensions; for example, if CGI scripts always have the extension.cgi, the Web server can be set to read all those files as CGI scripts. While this is useful and requested by many prepackaged scripts, it exposes the server to attacks if a remote user uploads executable code with the appropriate extension.

The user-submitted data is sent to the application via the standard input in the case of HTTP PUTs or POSTs. The Web server constructs a subset of the environment variables supplied and adds HTTP-specific data.

Uses

CGI is frequently used to process user input and provide relevant output. A CGI application that implements a wiki is an instance of a CGI program. The Web server runs the CGI application if the agent requests the name of an entry. The CGI software fetches the page's source for that item (if one exists), converts it to HTML, and outputs the result. The web server receives the CGI's output and sends it to the client device. The CGI software then populates an HTML Textarea or any other editing control with the page's information if the user agent selects the "Edit page" button. Finally, if the user agent presses the "Publish page" option, the CGI software saves the changed HTML as the source of that entry's page.

Security

CGI scripts run under the Web server's security context by default. With the release of the new CGI, various example scripts were included with the reference distributions of the NCSA, CERN, and Apache Web servers to demonstrate how shell scripts or C programs may be built to take advantage of it. PHF, a CGI software that developed a rudimentary phone book, was one such sample script.

This script, like many others back then, made use of a function called escape_shell_cmd(). It intended to sanitize its argument in the face of user input and then transmit it to the Unix shell to execute it in the Web server's security environment. The script did not properly sanitize all input and enabled additional lines to be given to the shell, allowing the execution of numerous commands. These commands' output was then displayed on the Web server. The performance of malicious commands by attackers is possible if the security environment of the Web server permits it.

That was the first widely publicized example of a new form of Web-based assault in which unsanitized data from Web users might lead to code activation on a Web server. Because of the sample code's deployment by default, assaults were common, prompting multiple security alerts in early 1996.

Alternatives

A Web server generates a new CGI process for each incoming HTTP request and terminates the CGI process once it has handled the HTTP request. Creating and terminating a process can require far more CPU and memory than just the actual work of producing the output, especially if the CGI program must still be parsed by a virtual machine. The ensuing demand from numerous HTTP requests can effortlessly overtake the Web server.

The overhead required in creating and destroying CGI processes can be decreased using the following techniques:

- CGI programs precompiled to machine code, for example, from C++ or C programs, instead of CGI programs translated by a virtual machine, for example, Python, Perl, or PHP programs.

- Web server extensions including Apache modules (e.g., mod_perl, mod_php, mod python), ISAPI plugins, and NSAPI plugins enable long-running application processes to be handled within the Web server and manage multiple requests. Web 2.0 enables data to flow from the client to the server even without the usage of HTML forms and without the user's knowledge.

- SCGI, AJP, and FastCGI enable long-running application processes that handle multiple requests outside the Web server. Every application process listens on a socket; for dynamic content, the Web server manages an HTTP request and transmits it to the socket via some other protocol (SCGI, AJP, and FastCGI), whereas static content is usually handled directly by the Web server. Because this method requires fewer application processes, it uses a smaller amount of memory than the Web server extension method. Application programs are not turning an application program into a Web server extension, they stay separate from the Web server.

- Jakarta EE runs Jakarta Servlet apps in a Web container to provide dynamic and potentially static content, eliminating the overhead of creating and deleting processes in favor of the significantly reduced overhead of establishing and destroying threads. That also exposes the developer to the Java SE library, on which the current version of Jakarta EE is built.

The appropriate configuration for any Web app is determined by application-specific details, traffic volume, and transaction complexity; the evaluation of these trade-offs is necessary to pick the most appropriate implementation for a given job and time budget. Web frameworks provide an option to interact with user agents via CGI scripts.